[Stan Lee, Roy Thomas, Gene Colan, Gil Kane, Michelle Robinson, Gerry Conway, John Romita Sr., Chris Claremont, Dave Cockrum, Kelly Sue DeConnick, Jamie McKelvie, Brian Bendis, Mike Allred, Peter David, Jack Kirby, Roger Stern, John Romita Jr., Scott Edelman, Al Milgrom,] Nicole Perlman, Meg LeFauve, Geneva Robertson-Dworet, Anna Boden, and Ryan Fleck, 2019

That’s a lot of names! And as the brackets indicate, most of them are uncredited: unless I’m blanking on something, this is the first Marvel Cinematic Universe property I have seen credited as “based on the Marvel Comics” with no particular creators listed. I can see why it might be difficult to determine who deserved the credit. Some of the folks I listed above created important supporting characters, but Captain Marvel alone accounts for a lot of them.

The original Captain Marvel was created by Stan Lee and Gene Colan; he debuted in an issue of Marvel Super-Heroes, an anthology series mostly made up of reprints, at the end of 1967. A few months earlier Stan Lee and Jack Kirby had spent a couple of issues of Fantastic Four introducing the Kree, a militaristic alien race so similar to us that most Kree could pass for human. (The blue ones had a tougher time.) The Kree were led by an artificial hive mind known as the Supreme Intelligence, whose chief project was to find a way to get the Kree out of the evolutionary dead end into which they had fallen. One of the Kree’s projects was to monitor human evolution via a robot called Sentry 459, which wound up in a clash with the Fantastic Four. Soon thereafter the Supreme Intelligence sent its chief law enforcement officer, Ronan the Accuser, to Earth to punish the Fantastic Four for their affrontery, but the F.F. got the better of him. And so the Supreme Intelligence sent in the troops under the command of Colonel Yon-Rogg, who sent down his subordinate Captain Mar-Vell in hopes that Mar-Vell would get himself killed on Earth so that Yon-Rogg could move in on Mar-Vell’s lover, a medic named Una. And that is as much setup as Stan did before turning over the reins to his protégé, Roy Thomas.

In his first issue, Thomas had Mar-Vell assume the identity of a human scientist named Walter Lawson, killed in his private plane as Yon-Rogg attempted to blast Mar-Vell from orbit. As Lawson, Mar-Vell was taken to Cape Canaveral to study the Kree Sentry salvaged by the military, where he met the Cape’s head of security, a tough young Air Force colonel named Carol Danvers. Carol became Marvel’s answer to Lois Lane, suspicious of the secretive “Walter Lawson” but enamored of the alien hunk who made a habit of saving her life and increasingly prioritized protecting humans over his Kree mission—to the point that he ditched his green and white Kree uniform for an outfit of red, yellow, and blue. This status quo lasted until the end of 1969, when Thomas returned after some time away to change things up a bit. Captain Mar-Vell was banished to the Negative Zone, but found a way to escape for a few hours at a time by linking up with former Hulk and Captain America sidekick Rick Jones. He directed Rick to put on a pair of “Nega-Bands” that, when clanked together, allowed the two to temporarily switch places, maintaining a psychic connection all the while. This was a radical enough change that the old supporting cast had to go, and Carol Danvers was written out by having her get zapped by Yon-Rogg (already responsible for Una’s death) and nearly get vaporized by an exploding “psyche-magnitron”; she is whisked to safety by Mar-Vell at the last moment. Carol was shuffled off to the hospital, and Rick and Mar-Vell entered the 1970s in a comic billed as “The Sensational NEW Captain Marvel”.

At this point the Marvel Universe had been around for less than ten years, but Marvel had already blown by rival DC Comics both in sales and critical acclaim. Ask anyone outside of comics fandom in the late 1960s what came to mind when asked about superheroes, though, and the answer was almost sure to be “Biff! Bam! Pow!”—because of the campy Batman TV series. Chalk one up for DC: a lot more people read comics then than read comics today, but the number was still minuscule compared to those who watched TV. And in 1975, DC scored another hit with the TV adaptation of Wonder Woman, which turned Lynda Carter into an icon of the era. Panic time at Marvel: Stan’s gang didn’t have a Wonder Woman! Marvel’s flagship superheroine was, emblematically enough, the Invisible Girl! The powers that be at Marvel knew that it was imperative to create an answer to Wonder Woman, but the problem was one I’ve discussed a few times: no one wanted to create a brand new character, watch it make billions for the company, and in return receive a standard paycheck for one script. And so, a derivative character it was! Wonder Woman wore red, yellow, and blue, so Captain Marvel looked like the best character to adapt. But Marvel couldn’t publish such a clear ripoff of Wonder Woman that it might risk litigation, so this spinoff character couldn’t look like Lynda Carter. That was okay, though, because who was an even hotter commodity than Lynda Carter? Farrah Fawcett! Of course, the ’70s were not just the era of Lynda Carter and Farrah Fawcett; they were also the era of Gloria Steinem, and so the Marvel brain trust tried to hitch its wagon to second-wave feminism by getting on board with the term of address Steinem had pushed into the mainstream, calling this new superhero Ms. Marvel. And to really burnish their feminist credentials, the creators—John Romita Sr. chief among them here—gave Ms. Marvel her namesake’s costume, added a scarf, and… removed all the material between her breasts and her boots save for a pair of blue panties. Her book hit the shops in the fall of 1976, and Gerry Conway took the lead on the writing side, establishing that Carol Danvers had been bathed in radiation when the “psyche-magnitron” exploded, giving her a pretty generic set of superpowers (flight, strength, durability); the gimmick was that she didn’t know it. She’d lost her job as head of security at Cape Canaveral for failing to capture Mar-Vell, then made a tidy sum from writing a book about the dark side of the aerospace industry, which she parlayed into a job as editor of “Woman Magazine” for $30,000/year ($160,000 today)… at which point she started to have blackouts. Simultaneously, a scantily clad superheroine with Farrah Fawcett hair started fighting crime in New York, but came up blank when asked such questions as what her name might be. “She isn’t your average super-heroine,” Conway wrote in a full-page editorial at the end of the first issue. “She doesn’t know who she is. Now, if you’ll think about that for a moment, you might see a parallel between her quest for identity, and the modern woman’s quest for raised consciousness, for self-liberation, for identity.” That raised the question of why this dude was selected to be the one to tell the story of “modern woman’s quest”. “Why didn’t a woman create Ms. Marvel?” he wrote. “A man is writing this book because a man wants to write this book: me. It’s a challenge. I want to do it.” Anyway, he lasted two issues.

Taking over was Chris Claremont, who was just starting his legendary run on what was still billed as “The All-New, All-Different X-Men”. His run on Ms. Marvel? Less legendary. He resolved Carol’s split personality, established that her power set was evolving as her body rebuilt itself as half-Kree after the explosion, filled in her backstory a little bit, and with Dave Cockrum got her into a new costume—but the book never took off and didn’t make it into the ’80s. To keep the character an active property, the decision makers at Marvel kicked Ms. Marvel over to the Avengers. But she didn’t do much there other than fill out the numbers. The Avengers’ book was largely written by committee around this time; Jim Shooter wrote a few issues, David Michelinie wrote a few, but fill-ins were frequent and many issues had their scripts credited to teams. Avengers #200 was credited to no fewer than four writers: Shooter and Michelinie along with George Pérez and Bob Layton. It was not long before none of them wished to have been credited. Because this was one of the key turning points for the character, and it was a fiasco. Recognizing that no one had any story arcs in mind for Ms. Marvel, the Avengers creators brainstormed ways to get her off the team. What did they go with? Why, they had her mysteriously fall pregnant; go through a full gestation period in less than a week; give birth to a boy who grows to adulthood in a matter of hours; listen to the boy explain that he was the son of the time-traveling villain Immortus, who had sired him by snatching a woman out of the past and spiriting her off to the timeless realm of Limbo, where he used “ingenious machines” to brainwash her into bearing his child, whom he named Marcus; and continue to listen to Marcus recount how, to escape Limbo, he had done the same thing to Carol, attempting to win her favors (“I had Shakespeare write you a sonnet”) before using Immortus’s hypnosis machines to complete the seduction and impregnate her with a version of himself. Carol’s reaction upon hearing this tale? “I still don’t know what I felt for you in Limbo, but some of that feeling still lingers,” she says, “and I think that just might be a relationship worth giving a chance.” And so Ms. Marvel headed off to Limbo with the “son” who’d raped her, while the Avengers, who had spent the previous three issues gushing about how Carol’s pregnancy was “great” and deserving of “congratulations”, shrugged and wished her a “happily ever after”. And again—Jim Shooter, editor-in-chief of Marvel Comics, not only signed off on this, but was credited as a contributor. His pal Bob Layton was too. The main Avengers team of Michelinie and Pérez not only helped with the plot but scripted and drew this. Everyone who looked at this story while it was in production let it continue on its path to the press. On 1980, July 15, it hit the shops.

And when Chris Claremont, who’d had custody of Ms. Marvel for over a year, saw what these guys had done to the character, he was livid. And he was in a unique position to do something about it. He had just wrapped up the Dark Phoenix Saga, and was the single hottest writer in the world of comics. Marvel could not afford to lose him. And so the higher-ups just had to sit there and eat it as Claremont wrote Avengers Annual #10 (1981), in which Carol Danvers, in furious tears, verbally rips the Avengers—and by extension, the creators of Avengers #200, including Claremont’s ultimate boss, Jim Shooter—apart. “Don’t any of you realize what happened months ago, what Marcus did to me?!?” she rages. “When I needed you most, you betrayed me.” As the Avengers stare at their shoes, she goes on, “There I was, pregnant by an unknown source […]—confused, terrified, shaken to the core of my being as a hero, a person, a woman. I turned to you for help, and I got jokes. […] Your concerns were for the baby, not for how it came to be—nor of the cost to me of that conception. You took everything Marcus said at face value. You didn’t question, you didn’t doubt. You simply let me go with a smile and a wave and a bouncy bon voyage. That was your mistake, for which I paid the price.” And note: this is not a young writer a generation later doing retcons to reflect that attitudes had changed. This is Marvel’s top dog immediately springing into action to impress upon his peers that their attitudes needed to change. In so doing, he helped to raise the consciousness of a generation of comic book readers—and he rescued the character of Ms. Marvel in real time. Gerry Conway had attempted to make Ms. Marvel a feminist icon by manufacturing moments in which she stood up to cartoon chauvinist J. Jonah Jameson. Claremont hadn’t actually done that much better in his own run on the Ms. Marvel book. But this organic conflict between a character designed to be a feminist icon and a staffroom full of real-life male writers who put her in a rape story without even seeming to realize they’d done so—Carol’s star turn in Avengers Annual #10 made the character.

Claremont reasserted control over the character after that and brought her over to X-Men, but she wasn’t a mutant, and he soon nudged her offstage as well. He had a new character he had ambitious plans for, a teenage girl named Rogue whose mutant power was to temporarily absorb superpowers, go too far with Ms. Marvel and permanently absorb her powers and psyche. Now neurologically disconnected from her memories and relationships, Carol erased any mention of herself from all official databases, went off to space with the X-Men, was experimented on by evil aliens, and in the process received a cosmic power-up. As “Binary”, she headed off into the depths of the galaxy with the Starjammers. She would go on to appear in a comic once every year or two. Until he left the company, every single one of these appearances was written by Chris Claremont. I guess Avengers Annual #10 scared all the other writers off!

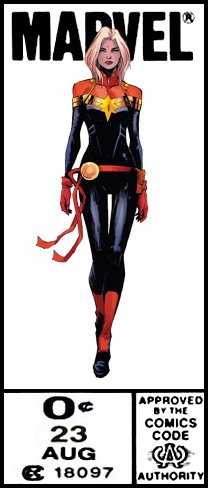

But time passed, the turn of the millennium approached, and a new generation of writers started to pop up in the credits of Marvel comics—writers who’d grown up on ’70s Marvel. When Kurt Busiek took the writing duties on the relaunched Avengers, he brought Carol back from space, powered her down a bit (though she kept the energy blasts), and put her back in the costume with the lightning bolt and trademark Cockrum sash—after all, it was Avengers-era Ms. Marvel he’d imprinted on, not Binary. (Unfortunately, his main contributions to the Carol Danvers mythos were to rename her “Warbird” and to give her a drinking problem, seemingly in service to moving Tony Stark’s character arc along from “recovering alcoholic” to “A.A. sponsor”.) When Brian Bendis got the green light to launch a series under Marvel’s new adults-only MAX imprint starring a new character he’d created, Jessica Jones, he pounced on the chance to bring in Carol Danvers as her best friend—and when he moved on to write multiple Avengers titles in the mid-’00s, he made Carol one of the mainstays… as Ms. Marvel, because, again, it wasn’t “Warbird” he’d imprinted on. He made her team leader. She got her own series back after a 27-year hiatus. She was on a trajectory to actually become Marvel’s answer to Wonder Woman, finally. But she did have that spinoff name. “Ms. Marvel”, when there was already a Captain Marvel? A bit like “She-Hulk” or “Batgirl”, right? Now here’s the thing. The companies behind superhero comics tend to keep names in circulation so as not to lose potentially valuable trademarks. The original Captain Marvel series was never a huge seller, and was canceled in 1970, brought back in 1972 as a bi-monthly, and canceled again in 1979. In 1982, the character was killed—by cancer!—in Marvel’s first official graphic novel, The Death of Captain Marvel by Jim Starlin. And that very same year, Roger Stern and John Romita Jr. introduced a completely new Captain Marvel, unrelated to the first: Monica Rambeau, who had the power to transform her body into any form of electromagnetic energy. She was immediately added to the Avengers, and stayed until 1988. But in the ’90s, Marvel editorial decided to give something closer to the original concept another shot, and gave the Captain Marvel name to Mar-Vell’s son Genis-Vell, even linking him to Rick Jones. Genis-Vell flamed out, and in the mid-’00s the name went to his sister Phyla-Vell. She was killed off at the beginning of the 2010s, a month after the second go-round of the Ms. Marvel book was canceled. So here multiple threads come together. The company wanted to position the Carol Danvers character as its Wonder Woman, but her spinoff name was a detriment to that. The company also needed to keep the Captain Marvel name alive, and not by bestowing it on another non-entity like Phyla-Vell. And so at long last Carol Danvers was relaunched by Kelly Sue DeConnick as Captain Marvel, with a new costume by Jamie McKelvie that reversed the colors of Mar-Vell’s. I didn’t collect the DeConnick book. But when I learned that her fellow Kelly, Kelly Thompson, would be writing the next volume of Captain Marvel, I did follow that one. A few years earlier she’d written Carol in A-Force. A-Force had a lot of recognizable characters, but always felt very peripheral to the rest of the Marvel Universe. Cut to 2019, and Kelly Thompson’s Captain Marvel felt like a core Avengers title—to the point that in the MCU, her absence was starting to feel conspicuous.

So, here she is! Or is she? Some MCU characters seem to have walked right off the pages of the comics (Nico Minoru, Alex Wilder); some redefine the character for the better (Tony Stark, Karolina Dean); some are misses, and just aren’t ever going to be who they claim to be (Bruce Banner, Natasha Romanoff). I was happy to find that the MCU Captain Marvel fell into the first category. The lobe of my brain that imprinted on all this stuff thought, yup, that’s Carol. As perfect a match as you could reasonably ask for. Maybe a younger version than I’m used to: even before she got powered up, she was put forward as having spent ten years in the Air Force before meeting Mar-Vell. In theory, she should be in her forties in current Marvel continuity, though she’s usually played as though she’s in her mid-thirties. But it stands to reason that she’d be a bit younger in her first MCU appearance than in her 1500th MU appearance.

What other ingredients are necessary to make this a Captain Marvel movie and not a Generic Superheroine in a Captain Marvel Suit movie? First, there’s the connection to the Kree; in the comics, Carol has recently been retconned to have not just been zapped by radiation from a Kree weapon, not just had her DNA reworked to make her a Kree hybrid, but to have had a Kree mother all along. Well, the Kree are certainly in evidence here. Carol is initially presented as full-blooded Kree—and that blood is blue. She wears a Kree uniform and fights a battle against the shape-shifting Skrulls (the Kree-Skrull War being a landmark in Avengers lore). She meets with the Supreme Intelligence. Your Kree needs will be met is I guess what I am saying. And if you do know the comics and find it fishy that her Kree pals are folks like Yon-Rogg and Att-Las and Minn-Erva—i.e., villains—that’s not necessarily a sign that things aren’t as they seem. Mar-Vell was a full-blooded Kree, after all, and went on missions with Yon-Rogg, and that didn’t disqualify him from being a Marvel superhero with his own magazine for over a decade. (We actually get a Mar-Vell here—a scientist rather than a warrior, with the Earth name of Wendy rather than Walter Lawson. Maybe an odd place for a shout-out to an electronic music composer, but okay.) However, as it turns out things are not as they seem, and MCU Carol is not full Kree, nor even half Kree, but a red-blooded human who’d spent her entire life on earth up until six years ago. Wouldn’t she remember that? Well…

…that’s another crucial ingredient of a Carol Danvers story: the blanked-out identity. It was key to the premise of the original Ms. Marvel (“She doesn’t know who she is”) and it was key to the end of her first stint as Ms. Marvel: mind-wiped by Rogue, she has the intellectual content of her memories restored by Professor X but her response is basically, “New soul, who dis?”. What we learn in this movie is that MCU Carol was an Air Force pilot who disappeared during a supposed test flight of an experimental faster-than-light engine developed by Mar-Vell / Lawson; in fact, the two of them were trying to keep the technology out of Kree hands, and after their plane is shot down and Mar-Vell is murdered by Yon-Rogg, Carol destroys the engine’s energy core and absorbs its power—leaving her comatose and amnesiac. So it’s easy enough for the Kree to pick her up, give her a blood transfusion, and when she wakes up, tell her that she’s a noble warrior hero of the Kree who had undergone a power-up procedure to serve as the ultimate weapon in the war against the Skrulls.

What other boxes need to be checked to make this a Captain Marvel movie? Air Force background, already covered. Cosmic energy powers, covered just now. Raped by her son—yeah, it turns out that the people investing $175 million in a popcorn movie elected to leave that bit out. Then there’s the question of making a personality match. The basics are pretty straightforward: toughened by a hardscrabble background, a trailblazer in male-dominated professions, a fair amount of life experience that allows her to be a mentor to younger women (e.g., Mary Jane Watson in the ’70s, Jennifer Takeda in the ’10s). But the storylines undermine her at every turn. As security chief for Cape Canaveral, she’s constantly reduced to a damsel in distress. As a top magazine editor, she’s a psychiatric case with a split personality. As an Avenger, first she’s portrayed as an ice queen, then she’s subjected to the heinous Marcus plotline, then she succumbs to alcoholism. By the time we get into the 21st century and she’s settling into her role as Marvel’s Wonder Woman, her feet of clay are a little sturdier, but her personality is still hard to pin down. As noted, in recent years she’s been written primarily by Kelly Thompson, and while Kelly Thompson is great, she does need to work on her ability to write a range of personalities. Just as Brian Bendis pretty much only writes “the Brian Bendis character”, Kelly Thompson pretty much only writes “the Kelly Thompson character”. She rarely passes the key test for dialogue in comics: read her conversations, and you generally can’t tell who’s speaking without following the tails on the speech balloons. But the Carol Danvers in this movie is basically “the Kelly Thompson character”, so that works out. She’s sassy and likeable. When she thinks she’s a Kree and crashes on Earth, the writers need to strike a delicate balance: it needs to be obvious that she’s not from around here, yet the Kree’s translation software and interplanetary reconnaissance are good, so she shouldn’t sound like a Conehead. She needs to be fluent in the language and culture of the spot where she lands, yet still come off as ever so slightly off. I’d say they pretty much nailed it!

Unfortunately, what they did not nail was telling a good story. Normally this is where I would complain about long stretches of loudness-war indecipherable CGI violence, but for once that’s not the main spectacle on offer; rather, the big gimmick is that this movie is set in 1995, which is played as a distant historical epoch, much the way Agent Carter played the 1940s. The filmmakers are clever about this revelation: since the movie starts on the other side of the galaxy, we have no time cues about what year it is on Earth, and we only discover that it isn’t the present when Carol crashes into… a Blockbuster Video. Which now signifies “vanished era” rather than “ubiquitous franchise”, though I have to consciously remember that that is the case. Because the ’90s are not a distant epoch to me. One way Captain Marvel hammers home “this is the past” is with clumsily deployed music cues: Garbage, No Doubt, R.E.M., Nirvana, Hole. That is indeed what you would have heard playing in my car back in 1995. It is also what you will hear playing in my car today. Well, that and Poppy. (Poppy is also a product of 1995, in a different way.) The filmmakers also make heavy use of that rejuvenating CGI technique we saw in Ant-Man; again, it didn’t work for me the way it probably did with most viewers because a Pulp Fiction-era Samuel L. Jackson doesn’t register for me as “what Samuel L. Jackson used to look like” but just as “what Samuel L. Jackson looks like”. There are also several shots of Windows 95, and—ha ha, you thought I was going to say I still use Windows 95, right? No, no. Windows 95 didn’t have Aero Glass yet. No 1995 vintage OS for me. My desktop has that fresh 2009 look.

Anyway, yeah, the story. Carol recovers her true memories, upending the initial setup: now the Kree are the bad guys, which somehow makes the Skrulls the good guys, apparently because they have children. Yon-Rogg captures Carol and forcibly sets up an interface between her and the Supreme Intelligence, who attempts to defeat her by reminding her that when she was little, she fell off her bike once. What the Supreme Intelligence didn’t count on was that young Carol didn’t spend the rest of her life lying on the pavement in tears but got up again, proving that on top of her cosmic energy powers she has the power of Grit™, against which the Kree Empire is helpless. Oh, and the filmmakers spend a lot of screen time on the painfully unfunny “Flerken” gag Kelly Sue DeConnick introduced to the mythos, apparently under the impression that those who picked up an issue of Captain Marvel would really prefer to be reading a Rocket Raccoon comic. See, it looks like a cat, but it’s not a cat, it’s a Flerken! Because “cat” sounds normal but “Flerken” sounds wacky! It’s like getting tapped to reboot the Batman franchise and deciding that what the first movie really needs is Bat-Mite. So, yeah—this version of Carol should make for a splendid addition to the MCU, but it’s too bad she didn’t arrive in a better vehicle.

The Punisher (season 2)

Gerry Conway, John Romita Sr., Ross Andru, [Len Wein, Larry Hama, Jason

Aaron, Mike Baron, Marc Guggenheim], and Steve Lightfoot, 2019

When I wrote about the first season of The Punisher, I said that I do not care for these ultraviolent shows that ask us to enjoy the fantasy that the world is full of brutal badasses who want to kill us but the most brutal badass of them all wants to kill them. Many do enjoy it: the Punisher, Frank Castle, was created as a villain, a dark reflection of superheroes that let Marvel writers at least begin to interrogate the idea of vigilantism, but readers were sufficiently pro-Punisher that eventually those writers had to throw up their hands and say, fine, you think this guy’s a hero? Then I guess we’ll write him as a hero. I do not think this guy’s a hero, and the idea of having to sit through a Punisher series really tested my commitment to MCU completism. So I was more than a little surprised to find that The Punisher was one of the best-made MCU shows. And the second season turns out to be even better than the first. It doesn’t sound like it should be, just based on a plot summary. The first season built up to Frank turning Billy “the Beaut” Russo into Jigsaw; now he actually gets a season to do Jigsaw stuff, but it does feel like a whole lot of tying up loose ends rather than its own storyline. (He also doesn’t look like Jigsaw, but just a guy with a few scratches. In Captain Marvel, Nick Fury came out worse after his encounter with the cat.) There is another storyline that puts forward the Mennonite, who appeared in a grand total of three issues of a non-MU comic called Punishermax, as a major player; he is backed by the season’s ultimate Big Bads, an elderly billionaire couple reminiscent of the Stromwyns, who have recently been the Big Bads over in the Daredevil comic. It’s not great material, but again, the creators here are skilled enough to make it more than hold its own with other MCU TV shows. They have Frank come to the rescue of a troubled teenage girl of whom he becomes very protective; this is a transparent way to bring reluctant viewers on board—oh, you’re not into his vengeance-fueled killing sprees? all right, how about killing sprees in the name of saving his beloved surrogate daughter?—and I was a total sucker for it.

One thing: the therapist working for Team Evil comes up with a plan based on the notion that the Punisher’s sense of identity relies on his insistence that he only kills those who deserve it. Make it look like he’s killed some innocent women, she tells Jigsaw, and he’ll fall apart. Which he does. Frank storms into Jigsaw’s HQ, defeats his goons, fires wildly at an escaping Jigsaw, shoots up the little office Jigsaw has run into, follows him inside, finds several women’s corpses, and becomes a basket case. Then proof emerges that, no, Jigsaw killed the women ahead of time, and with that assurance, Frank is fine. But, like… he could have been responsible! He did fire wildly into an office with no regard for the possibility that there might be innocents inside! I thought all the sports psychologists were agreed that outcome-oriented thinking was fundamentally fallacious and that process-oriented thinking was the superior alternative. Maybe murderous vigilantism psychologists take a different view.

Miss Meadows

Karen Leigh Hopkins, 2014

During my last visit to Ellie’s place we were scrolling through the streaming services and she happened across this one. Premise: Katie Holmes is the Punisher! She plays a first-grade teacher, in her mid-30s but carrying herself like a wide-eyed Disney princess, complete with CGI bluebirds trailing in her wake. She’s chipper in a Buffy-bot kind of way, right down to the old gag of taking everything people say literally. (A neighbor says that she wants to fix Miss Meadows up with a nice young man she knows because “I don’t want you to end up an old maid”; Miss Meadows replies, “That’s impossible. I don’t clean houses for a living, and I have no intentions to start domestication training.”) However, she also believes that the world is “a rotting cesspool” and has no qualms about using the gun in her purse to blow away the many crazed killers the film supplies to roam the town. “Toodle-oo!” she’ll chirp, and ka-blam. Then she’ll dance away, going tappity-tap as she does because, yeah, she wears tap shoes everywhere. Obviously, this premise is not played seriously. At least, it’s not played seriously at first. The weird thing is that, having taken such a broadly comic tone, the film then decides that it wants to be a Pattern 12 movie and redeem its earlier ludicrousness. Miss Meadows and her fiancé gulp down gallons of acting juice and have teary arguments that seem to be aiming for genuine pathos. This is such an unorthodox narrative move that I kind of have to admire it, but it doesn’t actually work. (Maybe one reason my mind went to Buffy-bot earlier is that her appearance is on a fairly short list of examples of storylines that encompass both total zaniness and real feeling.)

Death on the Nile

Agatha Christie, Anthony Shaffer, and John Guillermin, 1978

The Mirror Crack’d

Agatha Christie, Jonathan Hales, Barry Sandler, and Guy Hamilton, 1980

We also watched a couple of Agatha Christie movies made during the Carter administration. These are such small-scale stories that these adaptations felt to me like TV movies, and yet… the casts! The first of these has Mia Farrow, Jane Birkin, Olivia Hussey, David Niven, Maggie Smith, fuckin’ Bette Davis… and then the second one has Rock Hudson, Tony Curtis, Kim Novak, fuckin’ Elizabeth Taylor… I mean, sure, a lot of these folks were well past their primes, but still, those are some big names for a couple of little chamber pieces. (Angela Lansbury is actually in both: in the former, she plays a very broadly drawn alcoholic romance novelist, and in the latter she plays the detective, Miss Marple.) It seems pretty clear that these are attempts to recapture the success of the 1974 version of Murder on the Orient Express, which also crammed a lot of famous actors onto cramped sets to tell an Agatha Christie story; as such, they are interesting historical documents, but I don’t really have much to say about them. Probably the main thing I will remember is that when we watched Death on the Nile, Ellie was cheerful enough watching passenger after passenger get murdered, but was genuinely distraught at the sight of a cobra getting skewered. I’m about 99% sure this wasn’t a real cobra, but this might be the rare case in which she might prefer the CGI version, just to be sure.

|

|

|

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Tumblr |

this site |

Calendar page |

|||